The Essential Ingredient for Creating a Balanced Assessment System

The creation of a district- and schoolwide balanced assessment system requires change. And here, I’m not really talking about tinkering around the edges, making incremental adjustments.

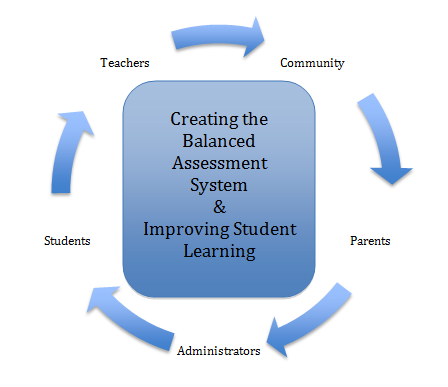

I’m talking about changing relationships—significantly changing the way superintendents, principals, lead teachers, teachers, staff, students, parents, and the community relate and work together.

To create and successfully enact a balanced assessment system, to pull it off, everyone will need to transform the way they think about schooling, their respective roles in schools, and the notion of leadership.

To create and successfully enact a balanced assessment system, to pull it off, everyone will need to transform the way they think about schooling, their respective roles in schools, and the notion of leadership.

And when these transformations are made, the answer to the question, “Who’s in charge,” undergoes a metamorphosis.

What do these changes look like? Changes from what to what?

The structure of our educational institutions — i.e., schools and districts — is largely organized around what Richard Elmore (1999) has called “loose coupling.” Here, Elmore suggests that educators who manage schools and districts “do not, in fact, manage the way its basic functions are carried out.

In school terms, administrators tend to have little to do with the ‘technical core’ of education” (p. 2).

More typically, administrators tend to “. . . manage the structures and the processes that surround instruction; they protect, or ‘buffer,’ the technical core from outside scrutiny or interference . . . in order to assure the public of the quality and legitimacy of what is happening in the technical core . . . the classroom” (Elmore, 1999, p. 2).

The unfortunate consequence of “loose coupling” is that teachers tend to work in isolation from each other and from their administrators as they (teachers) manage and are held accountable for the technical core and ultimately for the student learning that happens or does not happen in the classroom.

The result of this isolation is that administrators, too, tend to be isolated from teachers, the people most directly involved in addressing student learning within the classroom.

So, what model of educational leadership is most appropriate to the realities in schools and districts? What model eliminates the inherent isolation of both teachers and administrators? What model of leadership best assures that every student’s learning and development are optimized within the school and within the classroom?

If these are the questions, then the answers must explicitly link the educational leaders’ success to teachers’ success in the classroom and to every student’s success as a learner.

And if these linkages are to work in advancing student learning, we need to think about “leadership” as relational, not as an attribute of just one individual. From this perspective, leadership is defined as functioning through the “distribution” among and the participation of many (Donaldson, 2006; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001).

And if these linkages are to work in advancing student learning, we need to think about “leadership” as relational, not as an attribute of just one individual. From this perspective, leadership is defined as functioning through the “distribution” among and the participation of many (Donaldson, 2006; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001).

Successful leadership, therefore, becomes a social contract and a relationship among people, not something limited to the skill set or practices of one individual (Rost, 1993; Lezotte, 2005). According to Donaldson (2006), leadership is about “how I can help cultivate relationships among talented and well-intentioned educators and parents so that we all assure that every child learns” (p. 3).

Stated another way, effective and successful leadership is “a relationship that mobilizes people to fulfill the purposes of education” (ibid, p. 47).

What does research tell us about leadership?Most research, writing, and thinking on leadership place the leader in the center of the proverbial stage. However, when educational leadership is viewed as collective, co-active relationships, administrators, teachers, parents, other district/school staff, and community stakeholders also populate that center stage.

There has been and is strong support for a relational view of leadership. For example, Rost (1993) saw leadership as “an influence relationship among leaders and their collaborators who intend real changes that reflect their mutual purposes” (p. 7). In addition, Linda Darling-Hammond (1997) indicated that a collective relationship is replacing the individual as the crux of leadership. And according to Noddings (1984), “how good I can be is partly a function of how you — the other — receive and respond to me” (p. 6).

According to Donaldson (2006), “people joined in a leadership relationship will engage in working together to improve their effectiveness both individually and collectively” (p. 50).

In the end, effective, co-active leadership “takes a school full of people already in motion and enables them to alter their patterns of motion to improve their collective impact on children’s learning (Donaldson, 2006, p. 50).

The fundamental message here is a critical one: Creating an effective balanced assessment system, one that promotes student learning, is a collaborative, relational undertaking. And essential to this undertaking is the co-active leadership necessary to mobilize the entire community of stakeholders in the common purpose and pursuit of success for every single student.

References

Darling-Hammond, L. (1997). The right to learn: A blueprint for creating schools that work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Donaldson, Gordon A. (2006). Cultivating leadership in schools: Connecting people, purpose, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Elmore, Richard F. Building a new structure for school leadership. American Educator. American Federation of Teachers. Winter 1999-2000.

Lezotte, L. (2005). More effective schools: Professional learning communities in action. In R. DuFour, R. Eaker, & R DuFour (Eds.), On common ground: The power of professional learning communities (pp. 177-191). Bloomington, IN: National Educational Service.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rost, J. (1993). Leadership for the twenty-first century. New York: Praeger.

Spillane, J.; Halverson, R.; & Diamond, J. (2001. April). Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educational Researcher, 30(3), 23-28.